LC 00498: verschil tussen versies

Geen bewerkingssamenvatting |

Geen bewerkingssamenvatting |

||

| (4 tussenliggende versies door 2 gebruikers niet weergegeven) | |||

| Regel 1: | Regel 1: | ||

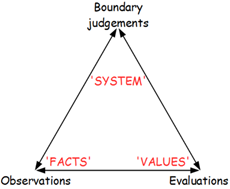

Posing the 12/24 (as-is & as-it-should-be) questions is not an exercise in which each box in the table is ticked automatically. It is a process of critical reflection in which one stakeholder’s insights influence the insights of the others, because things can be regarded from a different point of view or other value system. This makes critical reflection an instrument for a dialogue between stakeholders. The process of (once again) taking boundary judgements into account is visualised in CSH with the eternal triangle (see Figure 1). | |||

[[Bestand:Eternal triangle.png|gecentreerd|miniatuur|'''Figure 1:''' Eternal triangle.]] | |||

In CSH, a system is described according to a stakeholder’s interpretation, by means of boundary judgements. A boundary judgement is formed by objective, perceptible facts and stakeholders’ values. Boundary judgements, facts and values all interact with each other. An experienced CSH user will regard the other two aspects anew when one of them undergoes a change. Stakeholders in this process will get to see that their facts and values are relative notions. Other stakeholders can use equally valid, but different facts and values, depending on what their boundary judgements are. This truth paves the way to a constructive dialogue between stakeholders. With an iterative approach, using the eternal triangle instrument, a joint search can be made for improvements for situations by means of, eventually shared, or at least respected, boundary judgements and the facts and values that come with them. | |||

An easily recognizable example is not taking into account a group of stakeholders. In educational environments, teachers’ and students’ insights are not always considered, for example. People speak about others, instead of with others. If these groups are included, points of view can start shifting. A random example from practice, is that educationalists can be convinced that the students’ educational process must be tracked at every single stage, while teachers know from experience that more testing does not necessarily lead to better education. | |||

In short, involving different stakeholders can lead to different boundary judgements. As a result, different facts and value judgements will have to be included in the dialogue between stakeholders. | |||

In the case of student monitoring, teacher’s findings can be seen as factual material, just like hard numbers from written tests. The value system will then no longer just be based on objectively determined facts (the numbers tell the tale), but will be expanded with different value judgements that offer a more complete picture (for example: a student’s home situation and its effect on performance). | |||

{{LC Book config}} | {{LC Book config}} | ||

{{Light Context | {{Light Context | ||

| Regel 17: | Regel 18: | ||

|Sequence numbers=; | |Sequence numbers=; | ||

|Context type=Situation | |Context type=Situation | ||

|Heading= | |Heading=Changing Insights | ||

|Show referred by=Nee | |||

|Show edit button=Ja | |Show edit button=Ja | ||

|Show VE button=Ja | |Show VE button=Ja | ||

|Show title=Ja | |Show title=Ja | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{LC Book additional | {{LC Book additional | ||

|Preparatory reading= | |Preparatory reading=LC 00492 | ||

|Continue reading= | |Continue reading=LC 00496 | ||

}} | }} | ||

Huidige versie van 1 dec 2020 om 14:07

Posing the 12/24 (as-is & as-it-should-be) questions is not an exercise in which each box in the table is ticked automatically. It is a process of critical reflection in which one stakeholder’s insights influence the insights of the others, because things can be regarded from a different point of view or other value system. This makes critical reflection an instrument for a dialogue between stakeholders. The process of (once again) taking boundary judgements into account is visualised in CSH with the eternal triangle (see Figure 1).

In CSH, a system is described according to a stakeholder’s interpretation, by means of boundary judgements. A boundary judgement is formed by objective, perceptible facts and stakeholders’ values. Boundary judgements, facts and values all interact with each other. An experienced CSH user will regard the other two aspects anew when one of them undergoes a change. Stakeholders in this process will get to see that their facts and values are relative notions. Other stakeholders can use equally valid, but different facts and values, depending on what their boundary judgements are. This truth paves the way to a constructive dialogue between stakeholders. With an iterative approach, using the eternal triangle instrument, a joint search can be made for improvements for situations by means of, eventually shared, or at least respected, boundary judgements and the facts and values that come with them.

An easily recognizable example is not taking into account a group of stakeholders. In educational environments, teachers’ and students’ insights are not always considered, for example. People speak about others, instead of with others. If these groups are included, points of view can start shifting. A random example from practice, is that educationalists can be convinced that the students’ educational process must be tracked at every single stage, while teachers know from experience that more testing does not necessarily lead to better education.

In short, involving different stakeholders can lead to different boundary judgements. As a result, different facts and value judgements will have to be included in the dialogue between stakeholders.

In the case of student monitoring, teacher’s findings can be seen as factual material, just like hard numbers from written tests. The value system will then no longer just be based on objectively determined facts (the numbers tell the tale), but will be expanded with different value judgements that offer a more complete picture (for example: a student’s home situation and its effect on performance).

- Lees hiervoor:

- Lees hierna: