LC 00488: verschil tussen versies

Geen bewerkingssamenvatting |

Geen bewerkingssamenvatting |

||

| Regel 1: | Regel 1: | ||

Laws of Form showed in a formal way that the observer and observed coincide. In particular, the mark of distinction (˥) established the relation between distinction and indication: there cannot be a distinction without indication, and the other way round. The distinction severs a space in a marked and a unmarked state. An observer can observe only the marked side of the distinction in the act of observing, the other side is his blind spot. So, everyone has blind spots, which you can put to the test by yourself by observing the Necker cube and the Rubin vase. | |||

The cube can viewed from two perspectives, but not at the same time. | |||

[[Bestand:Cube I.png|gecentreerd|miniatuur|'''Figure:''' viewing a cube from two perspectives.]] | |||

If you have trouble seeing both perspectives, then the dotted, hidden edges might help to discern them. | |||

<accesscontrol>Access:We got to move</accesscontrol> | |||

[[Bestand:Vase silhouettes.png|gecentreerd|miniatuur|'''Figure:''' do you see a vase or do you see the silhouettes?]] | |||

At any one time, one view is perceived, whereas the other view is currently in your blind spot. Not only in the moment you perceive you have a blind spot, the very way how you perceive have its (implict) blind spots as well because of the distinctions you apply. You need someone else to point out your blind spots to you. | |||

Principle: you need someone else to point out your blind spots to you. | |||

[[Bestand:First and second order observation.png|gecentreerd|miniatuur|403x403px|Figure: first and second order observation.]] | |||

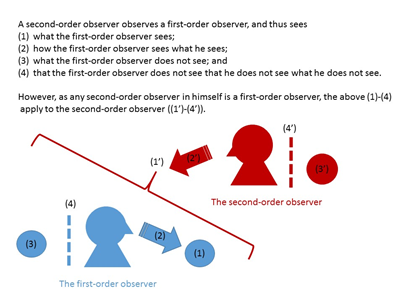

When you look at an object in the outside world, you are a first-order observer. A second-order observer observes how a first-order observer observes the outside world. So, the focus of attention is switched to ''how'' one looks, instead of ''what'' one sees. This is an important shift because it opens the possibility to thoroughly think through questions like: why is someone doing or saying things the way he does or says? The answers can be found in observing the distinctions that are made by taking a seconder-order point of view. | |||

[[Bestand:Cube IIa.png|gecentreerd|miniatuur|'''Figure:''' perspective nr. 1 to view the cube.]] | |||

[[Bestand:Cube IIb.png|gecentreerd|miniatuur|'''Figure:''' perspective nr. 2 to view the cube.]] | |||

You see the vase or the two silhouettes, but again, not at the same time. | |||

{{LC Book config}} | {{LC Book config}} | ||

{{Light Context | {{Light Context | ||

| Regel 12: | Regel 27: | ||

|Show title=Ja | |Show title=Ja | ||

|EMM access control=Access:We got to move, | |EMM access control=Access:We got to move, | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{LC Book additional | {{LC Book additional | ||

|Preparatory reading= | |Preparatory reading= | ||

|Continue reading= | |Continue reading= | ||

}} | }} | ||

Versie van 29 mei 2020 08:58

Laws of Form showed in a formal way that the observer and observed coincide. In particular, the mark of distinction (˥) established the relation between distinction and indication: there cannot be a distinction without indication, and the other way round. The distinction severs a space in a marked and a unmarked state. An observer can observe only the marked side of the distinction in the act of observing, the other side is his blind spot. So, everyone has blind spots, which you can put to the test by yourself by observing the Necker cube and the Rubin vase.

The cube can viewed from two perspectives, but not at the same time.

If you have trouble seeing both perspectives, then the dotted, hidden edges might help to discern them.

Dit is een beveiligde pagina.

At any one time, one view is perceived, whereas the other view is currently in your blind spot. Not only in the moment you perceive you have a blind spot, the very way how you perceive have its (implict) blind spots as well because of the distinctions you apply. You need someone else to point out your blind spots to you.

Principle: you need someone else to point out your blind spots to you.

When you look at an object in the outside world, you are a first-order observer. A second-order observer observes how a first-order observer observes the outside world. So, the focus of attention is switched to how one looks, instead of what one sees. This is an important shift because it opens the possibility to thoroughly think through questions like: why is someone doing or saying things the way he does or says? The answers can be found in observing the distinctions that are made by taking a seconder-order point of view.

You see the vase or the two silhouettes, but again, not at the same time.

- Lees hiervoor:

- Lees hierna:

Referenties

- Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Gregory Bateson, Jason Aronson Inc, 1 januari 1972.

- Objects as tokens for eigenbehaviours, H. von Foerster, Observing Systems, Systems Inquiry Series, pp. 274-285, 1 januari 1981.

- On the cybernetics of fixed points, Louis Kauffman, Cybernetics, 1 januari 2001.

- Processes and Boundaries of the Mind; Extending the Limit Line, Yair Neuman, Spriner Science Business Media, 1 januari 2003.

Hier wordt aan gewerkt of naar verwezen door: Gesprekken met betrokkenen voeren