Roots

Before diving into discussing EMM, it is helpful to say a few words about ontology and epistemology. Ontology can be understood from a philosophical as well as a computer science point of view. In philosophy, ontology is a branch of metaphysics studying the nature of reality (all that is or exists), and the different entities and categories within reality. Ontology has its counterpart in epistemology, which revolves around the study of knowledge and how to reach it. Ontology is often equated with reality, whereas epistemology is related to constructivism, i.e., the way the world is constructed in our minds.

Semantic Web

In computer science, especially in the field of semantic web and knowledge representation, ontology is defined as: a formal description of knowledge as a set of concepts within a domain and the relationships that hold between them. To enable such a description, the concepts that makes up an ontology need to be specified formally, such as individuals (instances or objects), classes, attributes and relations as well as restrictions, rules and axioms. As a result, ontologies do not only introduce a sharable and reusable knowledge representation, but they are also used to add new knowledge about the domain.

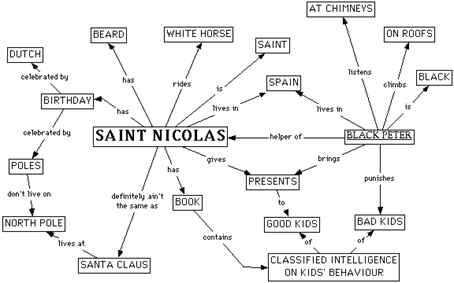

The semantic web is centered around the subject → predicate → object proposition. A proposition is a declarative sentence that is either true or false. For instance, Hans (subject) loves (predicate) music (object) is a proposition, which is true by the way for Hans who coauthored this writing. The role of subject and object can vary, that is, an object can take on the role of subject in another proposition, and vice versa. In this way, a cohesive network of propositions is formed. As such, a knowledge representation of a domain is established in which meaning is given by relating a concept to other (well-known) concepts. See, for example, the concept map of Saint Nicolas and his helper Black Peter. (We are aware of the political incorrectness of this example, and we have no intention whatsoever to offend anyone.)

The Expertise Management ontology (EMont) is a semantic web ontology. The domain that is described by EMont is human expertise (knowledge and skills) and how it is utilized collectively, which has an epistemological character. However, the cognitive structures with which humans perceive do have ontological components. For instance, the brain is made up of a network of neurons, which can be taken as really existing entities. So, EMont can also be considered from an ontological point of view describing realistic structures that enable expertise descriptions. This is most certainly not the last word that can be said about ontology and epistemology. For instance, a network of neurons is a system and because of the interconnectedness of neurons, new phenomena emerge, like consciousness, which cannot be attributed to individual neurons. So, what then is the nature of emerging phenomena such as consciousness? Is consciousness real, or is it part of our intangible mind?

Expertise and Knowledge

Knowledge is a concept that is difficult to grasp. It is often defined as justified true belief, that is, s knows that p if:

- p is true;

- s believes that p;

- s is justified in believing that p.

There are two problems with using this definition. First, the definition itself is problematic. Gettier showed that there are cases, the so-called Gettier cases (E.L. Gettier, 1 januari 1963), in which the three conditions hold, but these are not sufficient for knowledge. Second, the definition provides no clue how to structure knowledge.

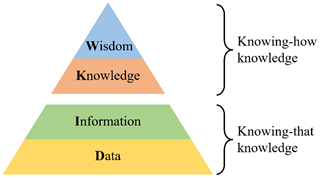

A more practical approach is to use the Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom (DIKW) (J. Abbas, 1 januari 2010) pyramid (see figure below). There are many explanations for interpreting the layers of the pyramid, see for example. For our purposes, we use the following interpretation:

- Data — Data as signals, symbols or facts;

- Information — Information is inferred from data in the process of answering interrogative questions (e.g., “who”, “what”, “where”, “how many”, “when”);

- Knowledge — Application of data and information; answers “how” questions, i.e. , understanding patterns;

- Wisdom — Understanding principles, learning from past actions.

Besides making the distinction between the aforementioned layers of the DIKW pyramid, it is also useful to distinguish between knowing-that (propositional) and knowing-how (procedural) knowledge. Knowing-that knowledge refers to the DI layers of the pyramid, whereas knowing-how knowledge refers to the KW layers.

Memory-Prediction Framework

In EMM, we are especially interested in the upper, knowing-how part of the DIKW pyramid, but the lower part is not neglected since applying knowing-how knowledge requires propositional, knowing-that knowledge. EMont is the ontology for describing knowing-how knowledge and the way knowledge of several actors can be applied in specific situations to achieve goals collectively. The key idea of EMont is based on the Memory-Prediction Framework (MPF) (J. Hawkins, 1 januari 2004), who has given an account of how the brain, in particular, the neocortex, is structured to produce intelligent behavior. Kurzweil has proposed a similar mind model (R. Kurzweil, 1 januari 2012). Both proposals are a bit speculative in places, however, their proposals are grounded in the seminal work of Mountcastle who discovered the columnar structure of the neocortex (V.B. Mountcastle, 1 januari 1957).

(Jeff Hawkins has recently written an update of his book (Jeff Hawkins, 1 maart 2021) in which the MPF is expanded with reference frames. Reference frames are akin to signs in cybersemiotics and related to fixed points (X = F(X)) in LoF. More to come on this.)

The columnar structures form a hierarchy of temporal patterns. At the lower level of the hierarchy, patterns are activated by the human senses by means of a self-associating pattern recognition process. That is, the stimuli of the senses match the beginning of a pattern, and the pattern then predicts the next stimuli. Once a lower-level pattern is recognized, it triggers a higher-level pattern, which on its turn predicts what is going to happen by activating lower-level patterns to anticipate next stimuli or triggers from lower-level patterns, and so on. In case stimuli from senses and triggers from patterns do not match a pattern any longer, a pattern is abolished.

The elegance of this model is that a single algorithm explains intelligent behavior. Lessons from the past are coded in patterns. These patterns are used to predict the (nearby) future. When predictions fail, new patterns take over and in this way the neocortex is continuously adapting to changing circumstances.

The pattern hierarchy is not fixed. Newly encountered experiences result in the creation of new patterns and adaptation of the hierarchical pattern structure. In short, we learn to handle in similar situations based on past experiences. The patterns become routines. For example, the routine of driving a car requires patterns that can be applied almost without consciously thinking. In fact, as experience grows, the patterns become more and more complex and are internalized as tacit knowledge (A. Lam, 1 januari 2000). For example, we know how to drive a car, but it is difficult to explain how we do it.

Of course, what we learn from experiences need not necessarily be the right way of doing things. The point is it is our personalized way of doing things. As such, the MPF gives an account of human activity systems. It suggests that human activity is organized hierarchically in terms of patterns, and that these patterns are shaped according to individual experiences, which gives an explanation for differences in worldviews. To put it differently in terms of Laws of Form and second-order cybernetics, the patterns can be seen as the distinctions that you make through experience in a reflexive domain. You are these distinctions. It is your way of perceiving and interacting with the world.

- Lees hiervoor:

- Lees hierna:

Referenties

- Tacit Knowledge, Organizational Learning and Societal Institutions: An Integrated Framework, A. Lam, Organization Studies , 21, 487-451, 1 januari 2000.

- Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?, E.L. Gettier, Analysis, 23:6, 121-123, 1 januari 1963.

- Structures for Organizing Knowledge: Exploring Taxonomies, Ontologies, and Other Schemas, J. Abbas, Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc., Chicago, 1 januari 2010.

- On Intelligence, J. Hawkins, Times Books, New York, 1 januari 2004.

- A thousand brains; a new theory of intelligence, Jeff Hawkins, Basic books, 1 maart 2021.

- How to Create a Mind: The Secret of Human Thought Revealed, R. Kurzweil, Viking Adult, New York, 1 januari 2012.

- Modality and Topographic Properties of Single Neurons of Cat’s Somatic Sensory Cortex, V.B. Mountcastle, Modality and Journal of Neurophysiology, 20, 408-434, 1 januari 1957.